I’ve been making web applications in Go for the past three years. The first project I joined used a flat hierarchy where all files are in the root of the project. When the project reached around 30 files we started grouping files into packages based on functionality. I made some mistakes and regularly ended up with cyclic dependencies. I searched and found structures that all looked very different from each other. None of them gave a satisfying guideline on how to structure an application in Go.

Another project I joined had been running for two years and had a very elaborate and completely different folder structure. It used code generation to generate wrappers around endpoints which did all the marshalling, unmarshalling, authentication, authorization, setting headers, parsing url parameters, query parameters and forms. It also generated test helpers, enumerations, and a whole system around event-sourcing. Basically everything that multiple frameworks and libraries would do for you. Needless to say, it took me while to discover where I could find what.

I was confused, how is it that there is no standard project structure?

Before I started working with Go I developed web applications in Python. First with Django, later on with Flask, CherryPy and Falcon. Django has thought me a structure that was helpful, it was easy to discover functionality and to find out where to put new code. Replicating a similar but stripped down version of that with the other Python frameworks was easy and straightforward.

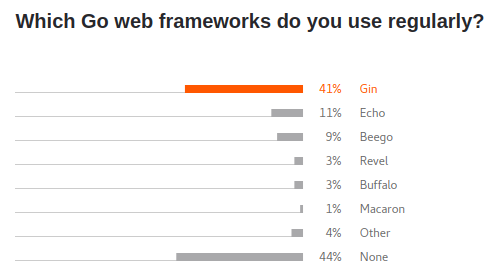

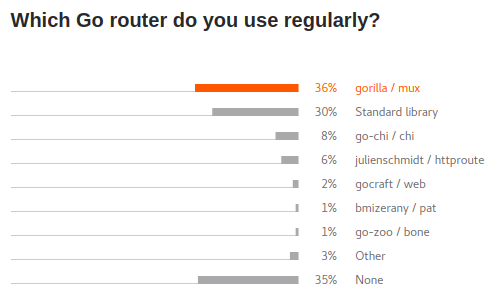

Django creates a folder and file structure for you. Go doesn’t do that. In fact, most Go developers recommend to not use a web framework at all. Jet Brains The State of Developer Ecosystem 2020 shows that a majority of developers do not use a web framework, and a third do not use a router. These statistics do include Go developers who do not develop web-related applications.

Over the years many great developers have written articles on structuring Go web applications. Most of these article arrived in my inbox via Golang Weekly, which is definitely a recommendation to subscribe to. Others I found via /r/golang and with some Google-Fu. I’m going over these articles and try to distil useful information.

Let’s start with Jon Calhoun. Jon is writing, in my humble opinion, the best series on structuring web applications in Go so far. You should definitely read the whole series. It’s so good, I’m going to use his series to establish a baseline and use that to look at the other articles.

Jon Calhoun

Series: Structuring Web Applications in Go

Right off the bat he asks the right question: Why can’t we settle on a single application structure in Go? I’m not going to reiterate over all of his points, as you should probably read his series before you continue reading here.

To summarize, Go aims for clarity, readability and explicitness. Frameworks usually give up on this in exchange for development speed. No framework means that you need to make your own decisions when it comes to structure.

Which structure is right for which situation? It depends. Or as Jon says, context is king. The size of your team, how much experience you have, correctness vs moving fast, microservices vs monoliths, and so on.

Article: Flat Application Structure

A flat application structure has all files in one single package.

| |

Key takeaways:

- You can stop worrying about how to organize things and get on with solving problems.

- Makes it easier to learn your application’s needs, your domain, or how to code in general.

- No cyclical dependencies.

- Naming collisions can be awkward.

- Create packages when the application grows.

- Won’t work forever, but probably longer than you think.

Article: Using MVC to Structure Go Web Applications

Model-View-Controller by layer has files separated into packages named by their function.

| |

models:

- should usually not import any other packages in your application

- database related logic, including retrieving relational data

- no html related code or http status codes

views:

- html/xml/json rendering

controllers:

- http handlers that parse incoming data

- call methods on the models

Key takeaways:

- MVC feels familiar and allows developers to make one less decision.

- Not everything is a model, view or controller, for example: middleware.

- If you face cyclical dependencies, there is a good chance you have broken things up too much.

- You don’t have to stick to the

models,viewsandcontrollersnames. For example,sql,html,http. - Models should not contain json tags, so you probably need to define resources more than once.

- The controllers can map a type in

modelsto a type inviewsand vice versa.

Article: Using MVC to Structure Go Web Applications

Model-View-Controller by resource has files separated into packages named by their resource.

| |

Key takeaways:

- Less common but still considered MVC.

Article: Using MVC to Structure Go Web Applications

Model-View-Controller by layer and resource has files separated into folders first by layer and then packages named after the resource.

| |

Key takeaways:

- Don’t do this, models tend to be relational so this results in cyclic dependencies

- Go does not have the concept of sub-packages. Each package is standalone.

Article: Moving Towards Domain Driven Design in Go

A web application structured using Domain Driven Design does not have a pre-defined folder structure. The folder structure below is not directly mentioned by Jon Calhoun, but it is how I interpreted the article.

| |

In software development, Domain Driven Design is a big topic. It doesn’t give much practical advise on folder structure, instead it helps you write software that can evolve over time. Many books and articles have been written on it over the past 20 years.

Jon asks, why don’t we just start here? Domain driven design has a fairly steep learning curve, not because the ideas are hard to grasp, but because you rarely learn where you went wrong in applying them until a project grows to a reasonable size. It takes time, effort and experience to do it right.

Key takeaways:

- DDD is for writing software that can evolve over time.

- Find a balance for decoupling. There is a point of diminishing returns where you are writing more and more code for adapters and plugging without getting any benefits.

- You don’t have a reasonable starting point for how to organize your code. With DDD you probably need to spend a great deal of time upfront deciding what your domain should be.

- Probably works better with a larger team and larger applications.

- Defining a domain model before using it is challenging.

- For a project that isn’t evolving, you likely don’t need to spend all the time decoupling your code.

- We very rarely swap out our database implementation, and if we do, we probably need to rethink a bit more.

- Probably don’t start decoupled, let code evolve over time.

Article: More Effective DDD with Interface Test Suites

The second article related to DDD written by Jon focuses more on the testing side. Using interface test suites is not specific to DDD but can be powerful when paired with it.

An interface test suite accepts an interface and runs tests against it. This is useful when you have multiple implementations for an interface and want to verify that all of them work accordingly. When applied to DDD, it means that you can create tests at the domain level and express the requirements for anyone who implements the interface.

General tips

Scattered throughout the articles of Jon are some general tips.

- Don’t use global variables. In Go web servers, requests are handled in goroutines. When they modify global variables you can get race conditions. Instead, encapsulate the data in an instantiated struct and inject it as a dependency where needed.

- In the same vein, global database connections are ill-advised, inject database connections into handlers.

Let’s end Jon’s part with this quote:

What this all means is that you should pick the structure that best suites your situation. If you are unsure of how complicated your application is going to be or are just learning, a flat structure can be a great starting point. Then you can refactor and/or extract packages once you have a better understanding of what your app needs. This is a point that many developers love to ignore - without building out an application it can often be hard to understand how it should be split up. This problem can also pop up when people jump to microservices too quickly. On the other hand, if you already know your application is going to be massive - perhaps you are porting a large application from one stack to another - then this might be a bad starting point because you already have a lot of context to work from.

William Kennedy

Article: Design Philosophy On Packaging

Packaging directly conflicts with how we have been taught to organize source code in other languages.

Purpose:

- Packages must provide, like

http,fmtandio, not contain likeutil,commonandhelpers.

Usability:

- Packages must be intuitive and simple to use.

- Packages must respect their impact on resources and performance.

- Packages must protect the user’s application from cascading changes.

- Packages must prevent the need for type assertions to the concrete.

- Packages must reduce, minimize and simplify its code base. This is the rule that Joh Calhoun is asking for in his DDD example. You can package and interface everything, but it should serve a purpose. That purpose is to reduce, minimize and simplify.

Portability:

- Packages must aspire for the highest level of portability.

- Packages must reduce setting policies when it’s reasonable and practical.

- Packages must not become a single point of dependency.

Article: Package Oriented Design

William believes that every company should have a Kit project. The packages of the Kit project should be made with the highest level of portablility and should be useful across multiple applications.

Each application project contains three root level folders. These are cmd/, internal/ and vendor/. There is also a platform/ folder inside of the internal/ folder, which has different design constraints from the other packages that live inside of internal/. Packages that are foundational but specific to the project belong in the internal/platform/ folder. These would be packages that provide support for things like databases, authentication or even marshaling.

Marcus Olsson

Series: Domain Driven Design in Go, Part 2, Part 3

Citerus developed the Java sample application for DDD. Marcus Olssen is a Go developer who ports the sample application to idiomatic Go.

He wants a structure with root-level domain packages. Packages should describe what they provide, not what they contain, so no domain and infrastructure packages. All packages are part of the root and are not hiding. He decided to not create a domain and application/services package, so it is easy to scan the root directory.

In DDD, objects that have an identity are called entities, if they don’t have an identity you call them value objects. To know if two objects are the same, you either compare the identities for entities or the values for value objects. In Go, when you want to compare objects to see if they are the same you have two options. Either you implement an Equals function for each struct, or you use the reflect.DeepEqual function. In this case he used the reflect option because implementing the Equals function did not feel useful enough.

In DDD, you want to keep value objects immutable in general. Go does not have immutable types. Instead, you can use pointer receivers for entities and value receivers for value objects.

Marcus chooses go-kit to add logging and metrics to the application.

Repository: github.com/marcusolsson/goddd

A great repository showcasing the Domain Driven Design (DDD) sample app in Go. It demonstrates:

- Bounded contexts

- Using interfaces to implement storage in the flavours in-memory and mongo

- Mocking

- Http tests

- Logging

- Metric collection

This repository feels like a goal I would like to work towards. One thing I would do differently is use a domain package as suggested by Jon Calhoun, but I do understand why Marcus has chosen not to create a domain package. This would avoid the awkward named imports like shipping "github.com/marcusolsson/goddd".

Ben Johnson

Article: Standard Package Layout

Ben starts by describing a three common, in his words, flawed approaches. These approaches line up perfectly with the structures that Jon Calhoun describes.

Monolithic package or flat structure. It usually works up to 10K SLOC.

The MVC approach by layer, and the MVC approach by resource both suffer from terrible naming and circular dependencies.

His approach:

- Root package is for domain types. The domain types should not depend on any other package in your application.

- Group subpackages by dependency, for example a sql package. Dependencies should be wrapped, including standard library dependencies.

- Use a shared mock subpackage.

- Main package ties dependencies together. Use dependency injection.

The approach of Ben Johnson is very similar to the DDD approach of Jon Calhoun. Domain types without dependencies, a separate mock package, and of course dependency injection.

Article: Structuring Applications in Go

Although this article it from 2014, it is still relevant. It contains four patterns:

- Don’t use global variables, use dependency injection.

- Separate your binary by using the

cmdfolder. - Wrap types for application specific context

- I think what he means with this one is that whenever you import types from a library or even from the standard library, and you are going to use this throughout your code, like the database example, wrap them so you can add your own logic.

- Don’t go crazy with subpackages. This is similar to the ‘start with a flat application structure’ method of Jon Calhoun.

If you’re writing Go projects the same way you write Ruby, Java, or Node.js projects then you’re probably going to be fighting with the language.

Series: WTF Dial

A great read on how to design a silly app and come to a very understandable and well-structured application that uses mocking.

Mat Ryer

Article: How I write HTTP services after eight years.

Mat gives great practical advise for write web services. He encapsulates dependencies in structs and sets up dependencies when preparing handlers. This results in not having any global dependencies and not using init() functions. Injecting dependencies also makes testing easier. The only mention of file structure is that he created a routes.go in each service which holds the routes.

It feels like Mat is mostly going for a flat application structure to keep things easy to understand. He is mostly focused on the best practises and testability of the application.

Peter Bourgon

Article: Go best practices, six years in

This article is from 2016 and feels a bit dated due to the mentioning of the GOPATH and the vendoring dependencies problems, but still contains very useful information.

Key takeaways:

- Use

cmdfor your binaries, usepkgfor all of your packages and Go code. - Use the root of your project for the rest like js files and configuration.

- Use environment variables for configuration, but also make them available as flags.

- Make dependencies explicit, use dependency injection.

- Use small interfaces to model dependecies.

- Loggers are dependencies, just like references to other components, database handles, commandline flags, etc.

Article: Theory of Modern Go

- No package level variables/global variables

- No

func init()

James Dudley

Article: How I Structure Web Servers in Go

Comes from C#. Focuses on discoverability as applications can live a long time in production.

- Describes much of the decoupling as described in the DDD examples of Jon Calhoun.

- Feels like it works well for microservices.

- Binds routing in one file/function

routebinds.go:BindRoutes(). - Puts endpoints for routes in separate files.

Iman Tumorang (bxcodec)

Articles: Trying Clean Architecture on Golang, Part 2, Part 3

Repository: github.com/bxcodec/go-clean-arch

Iman has worked on this repository for a number of years now and has written good blog posts about it. He originally aimed at making a structure which is in line with Uncle Bob’s Clean Code Architecture. The first iteration of the project had multiple dependencies in his models which lead to cyclic imports.

The second iteration moved all models together into a single package. He moved interfaces for repositories and usecases one level higher.

The third iteration includes a structure which is much more DDD oriented and which involves a domains package. The domains package contains all models and interfaces that are used throughout the other packages. It showcases great usage of dependency injection and mocks. One thing I would like to see in the next iteration is treating logging as a dependency as well.

Ben Cane

Presentation: How I Structure Go Packages

- He makes a distinction between

- in-app packages: as part of a greater application. Often created to isolate functionality rather than reuse it.

- stand alone: share functionality across many applications.

- Packages should solve one problem domain, be reusable by default, and individually testable.

- All packages in the top-level under their own package names.

- The primary file in each package should have the same name as the package.

- Group file by functionality

- Avoid creating a

constants.go,types.goorutils.go. This is similar to not creating autilspackage. - If you find yourself using

init()to create async.Mapor initialize other things. Ask yourself, if I run multiple tests in parallel, will it break? - Packages should solve one problem, utilities is not a problem.

- Stick to

New()orDial()for creating instances of structs. - Use dependency injection, config and logging are dependencies too.

Kat Zień

Repository: github.com/katzien/go-structure-examples

Kat has given a number of great talks for if you prefer to digest content via video and audio. She goes over the same structures as Jon Calhoun. The linked repository contains links to her videos.

Windi Chandra

Article: Domain-Driven Design in Go

Windi takes the DDD approach quite literally and structures the folders according to the theory. The folders in the root are named after the 4 layers described in DDD. Within the domain package there are four packages named after the terms that are used in DDD. By separating the domain I can imagine a situation in which this can lead to circular dependencies between entities and value objects. There is a usage of, as recognized by Windi, flawed singleton pattern where global variables are used instead of dependency injection.

| |

Conclusion

I have learned a lot, reading through all these articles and repositories and watching videos. I will write another article about the structure that I’m going to use for my next project.